The usage of MDF

Medium-density fibreboard (MDF) is an engineered wood product made by breaking down hardwood or softwood residuals into wood fibres, often in a defibrator, combining it with wax and a resin binder, and forming it into panels by applying high temperature and pressure. MDF is generally more dense than plywood . It is made up of separated fibres, but can be used as a building material similar in application to plywood. It is stronger, and more dense, than particle board.

The name derives from the distinction in densities of fibreboard. Large-scale production of MDF began in the 1980s, in both North America and Europe.

Physical properties

Over time, the term MDF has become a generic name for any dry process fibre board. MDF is typically made up of 82% wood fibre, 9% urea-formaldehyde resin glue, 8% water and 1% paraffin wax. And the density is typically between 500 kg / m3 (31 lb / ft3) and 1,000 kg / m3 (62 lb / ft3). The range of density and classification as light, standard, or high density board is a misnomer and confusing. The density of the board , when evaluated in relation to the density of the fibre that goes into making the panel, is important. A thick MDF panel at a density of 700–720 kg / m3 may be considered as high density in the case of softwood fibre panels, whereas a panel of the same density made of hard wood fibres is not regarded as so. The evolution of the various types of MDF has been driven by differing need for specific applications.

Types

There are different kinds of MDF (sometimes labeled by colour):

- Ultralight MDF plate (ULDF)

- Moisture resistant is typically green

- Fire retardant MDF is typically red or blue

Although similar manufacturing processes are used in making all types of fibreboard, MDF has a typical density of 600–800 kg / m³ or 0.022–0.029 lb / in3, in contrast to particle board (160–450 kg / m³) and to high- density fibreboard (600–1,450 kg / m³).

Manufacturing

Medium-density fibreboard output in 2005

In Australia and New Zealand, the main species of tree used for MDF is plantation-grown radiata pine; but a variety of other products have also been used, including other woods, waste paper and fibres. Where moisture resistance is desired, a proportion of eucalypt species may be used, making use of the endemic oil content of such trees.

Chip production

The trees are debarked after being cut. The bark can be sold for use in landscaping, or used as biomass fuel in on-site furnaces. The debarked logs are sent to the MDF plant, where they go through the chipping process. A typical disk chipper contains 4–16 blades. Any resulting chips that are too large may be re-chipped; undersized chips may be used as fuel. The chips are then washed and checked for defects. Chips may be stored in bulk, as a reserve for manufacturing .

Fibre production

Compared to other fibre boards, such as Masonite, MDF is characterised by the next part of the process, and how the fibres are processed as individual, but intact, fibres and vessels, manufactured through a dry process. The chips are then compacted into small plugs using a screw feeder, heated for 30–120 seconds to soften the lignin in the wood, then fed into a defibrator. A typical defibrator includes two counter-rotating discs with grooves in their faces. Chips are fed into the centre and are fed outwards between the discs by centrifugal force. The decreasing size of the grooves gradually separates the fibres, aided by the softened lignin between them.

From the defibrator, the pulp enters a 'blowline', a distinctive part of the MDF process. This is an expanding circular pipeline, initially 40 mm in diameter, increasing to 1500 mm. Wax is injected in the first stage, which coats the fibres and is distributed evenly by the turbulent movement of the fibres. A urea-formaldehyde resin is then injected as the main bonding agent. The wax improves moisture resistance and the resin initially helps reduce clumping. The material dries quickly in the final heated expansion chamber of the blowline and expands into a fine, fluffy and lightweight fibre. This fibre may be used immediately, or stored.

Sheet forming

Dry fibre gets sucked into the top of a 'pendistor', which evenly distributes fibre into a uniform mat below it, usually of 230–610 mm thickness. The mat is pre-compressed and either sent straight to a continuous hot press or cut into large sheets for a multi-opening hot press. The hot press activates the bonding resin and sets the strength and density profile. The pressing cycle operates in stages, with the mat thickness being first compressed to around 1.5× the finished board thickness, then compressed further in stages and held for a short period. This gives a board profile with zones of increased density, thus mechanical strength, near the two faces of the board and a less dense core.

After pressing, MDF is cooled in a star dryer or cooling carousel, trimmed and sanded. In certain applications, boards are also laminated for extra strength.

The environmental impact of MDF has greatly improved over the years. Today, many MDF boards are made from a variety of materials. These include other woods, scrap, recycled paper, bamboo, carbon fibres and polymers, forest thinnings and sawmill off-cuts.

As manufacturers are being pressured to come up with greener products, they have started testing and using non-toxic binders. New raw materials are being introduced. Straw and bamboo are becoming popular fibres because they are a fast-growing renewable resource.

Comparison with natural woods

MDF does not contain knots or rings, making it more uniform than natural woods during cutting and in service. However, MDF is not entirely isotropic, since the fibres are pressed tightly together through the sheet. Typical MDF has a hard, flat, smooth surface that makes it ideal for veneering, as there is no underlying grain to telegraph through the thin veneer as with plywood. A so-called "Premium" MDF is available that features more uniform density throughout the thickness of the panel.

MDF may be glued, doweled or laminated. Typical fasteners are T-nuts and pan-head machine screws. Smooth-shank nails do not hold well, and neither do fine-pitch screws, especially in the edge. Special screws are available with a coarse thread pitch, but sheet-metal screws also work well. MDF isn't susceptible to splitting when screws are installed in the face of the material but, due to the alignment of the wood fibres, may split when screws are installed in the edge of the board without pilot holes.

- Consistent in strength and size

- Shapes well

- Stable dimensions (less expansion and contraction than natural wood)

- Takes paint well

- Takes woodglue well

- High screw pull-out strength in the face grain of the material

Drawbacks

- Denser than plywood or chipboard

- Low grade MDF may swell and break when saturated with water

- May warp or expand in humid environments if not sealed

- May release formaldehyde, which is a known human carcinogen and may cause allergy, eye and lung irritation when cutting and sanding

- Dulls blades more quickly than many woods. Use of tungsten carbide edged cutting tools is almost mandatory, as high speed steel dulls too quickly

- Though it does not have a grain in the plane of the board, it does have one into the board. Screwing into the edge of a board will generally cause it to split in a fashion similar to delaminating

Applications

Loudspeaker enclosure being constructed out of MDF

MDF is often used in school projects because of its flexibility. Slatwall panels made from MDF are used in the shop fitting industry. MDF is primarily used for indoor applications due to its poor moisture resistance. It is available in raw form, or with a finely sanded surface, or with a decorative overlay.

MDF is also usable for furniture such as cabinets, because of its strong surface.

Safety concerns

When MDF is cut, a large quantity of dust particles are released into the air. It is important a respirator be worn and that the material is cut in a controlled and ventilated environment. It's good practice to seal exposed edges to limit emissions from binders contained in this material.

Formaldehyde resins are commonly used to bind together the fibres in MDF, and testing has consistently revealed that MDF products emit free formaldehyde and other volatile organic compounds that pose health risks at concentrations considered unsafe, for at least several months after manufacture. Urea-formaldehyde is always being slowly released from the edges and surface of MDF. When painting, it is a good idea to coat all sides of the finished piece in order to seal in the free formaldehyde. Wax and oil finishes may be used as finishes but they are less effective at sealing in the free formaldehyde.

Whether these constant emissions of formaldehyde reach harmful levels in real-world environments is not yet fully determined. The primary concern is for the industries using formaldehyde. As far back as 1987, the US EPA classified it as a "probable human carcinogen" and, after more studies, the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), in 1995, also classified it as a "probable human carcinogen". Further information and evaluation of all known data led the IARC to reclassify formaldehyde as a "known human carcinogen "associated with nasal sinus cancer and nasopharyngeal cancer, and possibly with leukaemia in June 2004.

According to International Composite Board Emission Standards (ICBES), there are 3 European formaldehyde classes, namely: E0, E1 and E2. This classification is based on the measurement of formaldehyde emission levels. For instance, E0 is classified as having less than 3 milligrams of formaldehyde out of every 100 grams of the glue used in particleboard and plywood fabrication. E1 and E2, conversely, are classified as having 9 and 30 grams of formaldehyde per 100 grams of glue respectively. All around the world variable certification and labeling schemes are there for such products that can be explicit to formaldehyde release, like that of Californian Air Resources Board (CARB).

Veneered MDF

Veneered MDF provides many of the advantages of MDF with a decorative wood veneer surface layer. In modern construction, spurred by the high costs of hardwoods, manufacturers have been adopting this approach to achieve a high quality finishing wrap covering over a standard MDF board. One common type uses oak veneer. Making veneered MDF is a complex procedure, which involves taking an extremely thin slice of hardwood (approx 1-2mm thick) and then through high pressure and stretching methods wrapping them around the profiled MDF boards. This is only possible with very simple profiles because otherwise when the thin wood layer has dried out, it will break at the point of bends and angles.

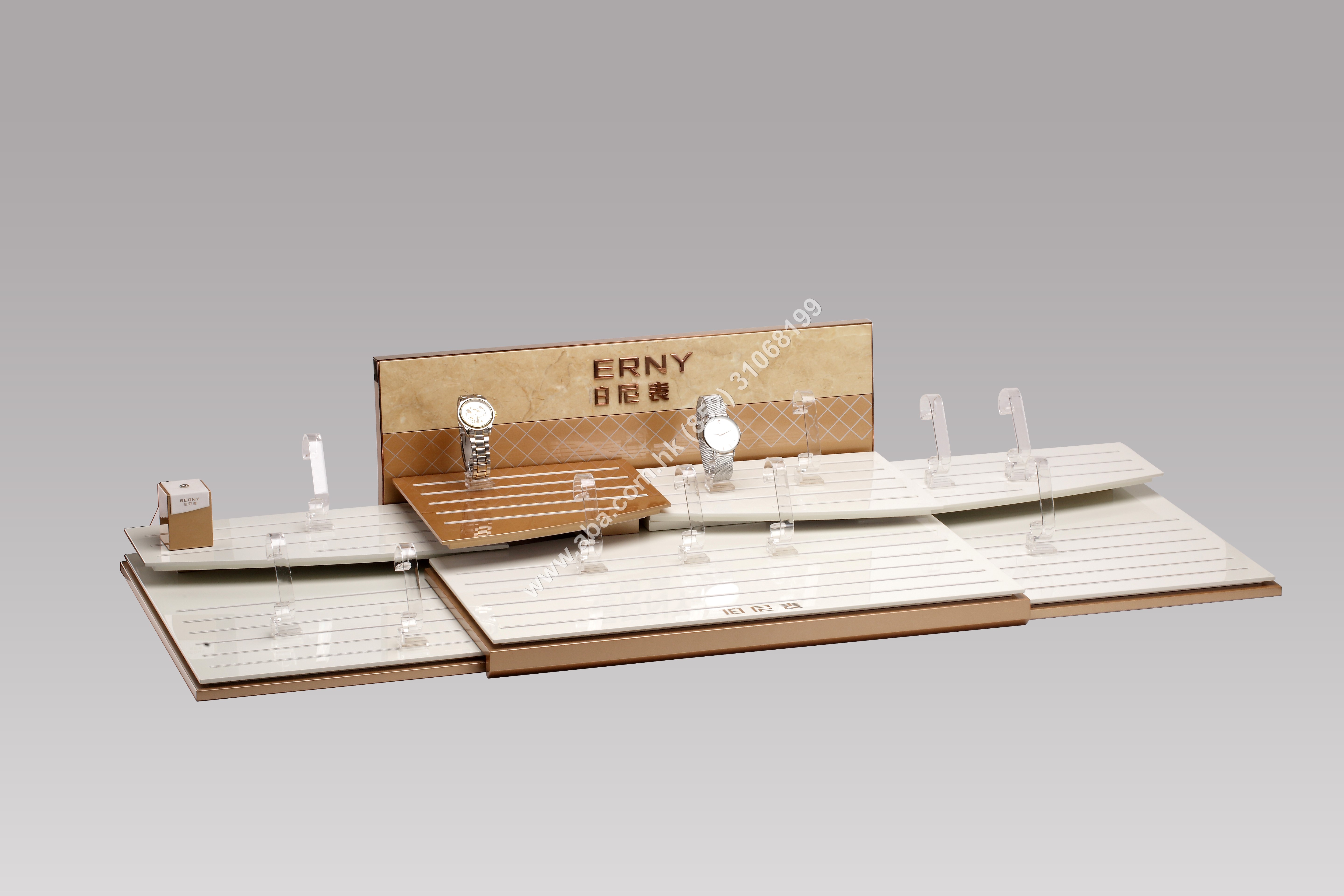

Because MDF has excellent processability, it can solve the problem of easy moisture after treatment. With different paint processes, the finished product is noble and elegant, simple and beautiful. Therefore, in various high-consumption product markets, such as famous brand watches, precious jewellery, etc., we can see mdf as a product display shelf in the window. In terms of high-end product display, MDF has become the best choice.

As a professional display equipment manufacturer, we have many years of experience in manufacturing acrylic display racks, display cabinets, and shelves. If you want to get more data in this regard, please feel free to contact us.